Treatment planning serves as the foundation of effective interventions for young people who have engaged in harmful behaviors. As professionals in the sexual abuse prevention field, our approach to creating and implementing these plans significantly impacts client outcomes and community safety. Drawing from evidence-based practices and contemporary research, combined with recommendations shared by the presenters of recent online trainings conducted by Safer Society’s Continuing Education Center (the CEC), this post explores how thoughtful, individualized treatment planning can transform young people’s lives while also reducing the risk that they will harm again.

Assessment is the Foundation

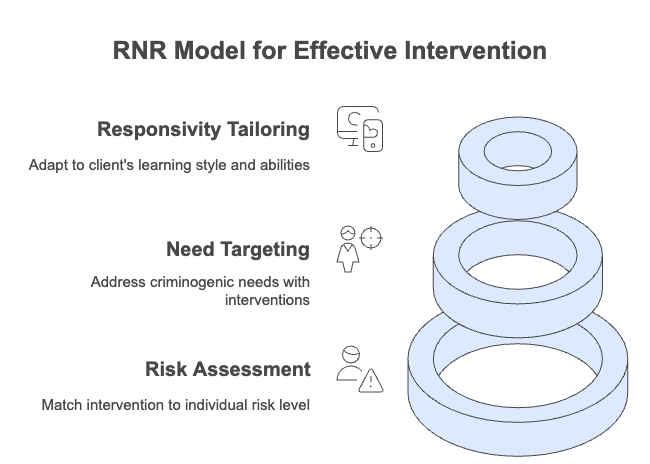

Effective treatment planning begins with comprehensive, developmentally appropriate assessment. The risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model is the most widely used, evidence-based framework for guiding treatment planning with individuals who have engaged in harmful behaviors. While originally developed for adults, the RNR model can be effective with adolescents, provided it is thoughtfully adapted to their unique developmental needs.

- Risk: Intervention intensity should match the individual’s risk of reoffending. For adolescents, risk can change rapidly due to ongoing development, so reassessment should occur more frequently (every 3–6 months) than with adults.

- Need: Treatment should focus on dynamic, changeable factors that contribute to harmful behavior. With youths, this includes not only criminogenic needs but also developmental, family, peer, and school-related factors.

- Responsivity: Interventions must be tailored to the young person’s learning style, cognitive abilities, cultural background, and readiness for change. Adolescents benefit most from approaches that are engaging, strengths-based, and involve family or caregivers.

When working with young people, it’s especially important to remember the advice that was shared by Katie Gotch, LPC, CCSOT, ATSA-F in one of her CEC trainings: “Youths are not mini adults. They require specialized approaches for assessment, treatment, and management that are developmentally appropriate.”

Building on the RNR model, treatment planning also emphasizes the importance of identifying and nurturing protective factors. Tools such as the PROFESOR (Protective + Risk Observations For Eliminating Sexual Offense Recidivism) help clinicians identify and build upon strengths while addressing areas of concern. This balanced approach is particularly important when working with adolescents who have low rates of sexual recidivism and a high potential for positive change.

Once a comprehensive assessment is complete, the next step is to establish a therapeutic alliance that supports the client’s journey.

Building the Therapeutic Alliance with Young People

At the center of successful treatment lies the therapeutic relationship. Research shows that a strong working alliance between client and clinician significantly improves outcomes across all types of therapy. This alliance becomes even more critical when working with mandated clients or those who may be ambivalent about change. By creating a safe, non-judgmental space, clinicians foster honest communication and authentic engagement. For clients who have caused harm, this alliance creates conditions where they can acknowledge their actions without being defined solely by them.

David Prescott and Seth Wescott—CEC training moderators and regular presenters—emphasize that building an effective therapeutic alliance requires viewing treatment as something done “for and with” clients rather than “to” them. Creating a collaborative partnership should feel like “choreography or a dance, not wrestling.” A strong alliance is grounded in deeply understanding the client’s perspective—asking what they long for, what’s missing in their lives, and what matters to them. Creating a safe environment is foundational for progress, especially for youths from backgrounds where trust is often lacking. Seth notes that “many youths have been invalidated for so long,” highlighting the role of validation in reducing shame and guilt, which have “no place in the therapeutic environment.”

Additionally, David, Seth, and Katie advocate for establishing a “culture of feedback,” where clients can openly discuss what isn’t working. When clients can comfortably provide negative feedback, it demonstrates what Katie calls “a room full of trust,” indicating a truly successful therapeutic engagement.

Collaborative Goal Setting

Treatment planning works best when it is a collaborative process that actively involves the client and their support network. A collaborative approach acknowledges the client’s agency in their own treatment journey, creating investment and meaning that increase the likelihood of positive outcomes.

Seth emphasizes this when he says that the core of effective treatment strategies is “collaborative, collaborative, collaborative.” He notes that “this is a partnership” where we’re “inviting [clients] into the discussion” and “into the process of change.”

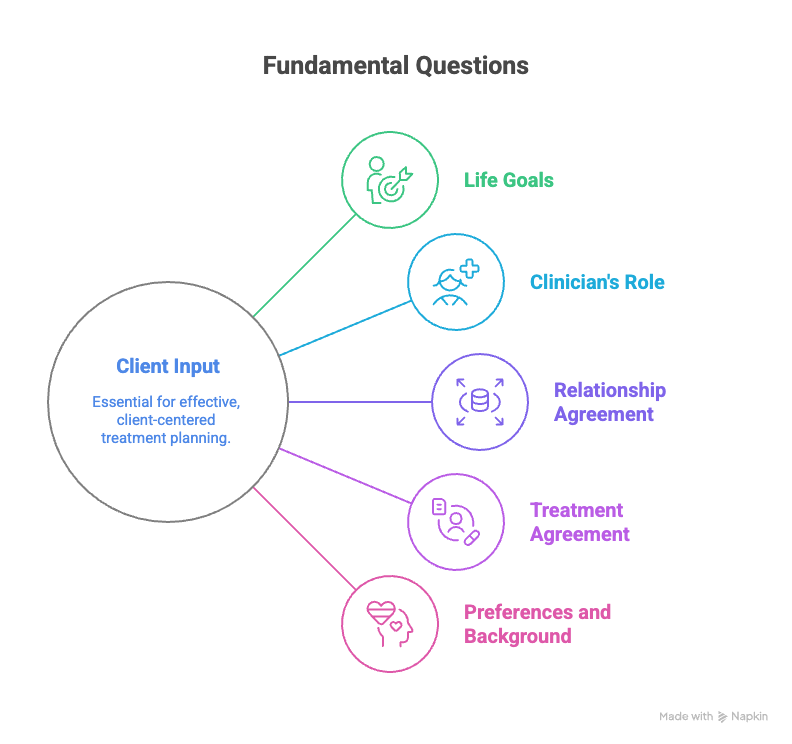

As David explains, simply establishing treatment goals without client input carries significant risks. He suggests starting by asking the client some fundamental questions:

- What are your goals in life?

- As a clinician, how do I fit into your life?

- Is there agreement on the nature of our relationship?

- Is there agreement on how treatment will work?

- What are your strong preferences, cultural considerations, and religious background?

Addressing Trauma and Building Strength in Adolescents

Many youths who have engaged in harmful behaviors have histories of trauma and adversity. Effective treatment plans must recognize these experiences while focusing on building resilience and strengths.

“Shame has no place in the therapeutic environment… Instead, we want to reduce those feelings of failure, of shame, decreased motivation. A lot of them come in with that. And so how can we build on the strengths that they already have by promoting that honesty, by promoting the disclosure, allowing them to feel comfortable in treatment, creating a safe space for them.” – Seth Wescott, Best Practices in Treatment Planning for Adolescents Who Have Sexually Abused

Moving Beyond Labels: Person-First Approaches

One of the most significant shifts in modern treatment planning involves the conscious use of person-first language. This approach recognizes the full humanity of clients beyond the behaviors that brought them into treatment.

“What we know from the research is that labels do not serve our shared goals of rehabilitation or change. They can create barriers for clients to move forward when they internalize those negative labels. And the public and policymakers actually respond differently when we use first-person or person-first language versus labels for our clients.” – David Prescott, Best Practices in Treatment Planning for Adolescents Who Have Sexually Abused

This perspective extends beyond verbal interactions to written documentation, including treatment plans themselves. By describing “youth who have engaged in harmful sexual behaviors” rather than applying stigmatizing labels, we create space for positive change and identity development.

“I do not want my clients to internalize the label of sex offender as part of who they are in their identity. I want them to understand that they have caused harm and to work with them to not cause harm again. And this includes in the printed document of a treatment plan.” David Prescott, Best Practices in Treatment Planning for Adolescents Who Have Sexually Abused

Overcoming Common Challenges

Developing effective treatment plans for adolescents who have sexually harmed requires navigating several complex challenges. Professionals must balance the need for accurate, developmentally appropriate assessments with the importance of engaging families and managing often limited resources. Below are some common obstacles faced in this work, along with practical strategies to overcome them and enhance treatment outcomes:

- Outdated assessment tools: Update or adopt tools that are developmentally informed and reflect the unique needs of adolescents, such as those that emphasize protective factors and consider the adolescent’s learning style, motivation, and mental health needs.

- Engagement difficulties: Use strategies to enhance family involvement, such as setting expectations for family participation at intake, using motivational interviewing to address reluctance, and providing ongoing education and support to families throughout the treatment process. Parents can benefit from educational sessions on topics like healthy sexuality, pornography, and social media—subjects that families often avoid discussing yet are essential for fostering open communication and supporting positive outcomes.

Despite these obstacles, maintaining a client-centered focus remains essential:

“The more we can individualize things, the more we can make it about what is going to move this client in a healthy, positive direction and accomplish pro-social goals, allowing them to develop and flourish and turn into the people that we want them to be instead of the people that we fear; that’s the direction that we need to go.” Seth Wescott, Best Practices in Treatment Planning for Adolescents Who Have Sexually Abused

Conclusion and Professional Development Resources

Thoughtful, individualized treatment planning is fundamental to promoting safety, accountability, and positive outcomes for adolescents who have engaged in sexually harmful behaviors. By integrating person-first language, collaborative goal setting, and strengths-based approaches, professionals can move beyond risk management to foster genuine healing and growth for clients and their communities.

To support clinicians in this important work, Safer Society’s Continuing Education Center offers trainings designed to enhance the effectiveness of treatment with adolescents:

- Best Practices in Treatment Planning for Adolescents Who Have Sexually Abused

- Assessing Adolescents with Sexually Abusive Behaviors

- Overcoming Common Issues in the Treatment of Adolescents Who Have Engaged in Sexually Harmful Behavior

- Using the Good Lives Model with Adolescents and Young Men Who Have Harmed Others