September is Suicide Prevention Month, when mental health professionals, advocates, and communities unite to share resources that save lives. This year, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA)’s Week 3 theme highlights collaborative safety planning as a tool that gives people “a sense of control and of hope” during a suicidal crisis. A recent training titled “The Safety Planning Intervention in Suicide Prevention” by Mark Margolis—Suicide Prevention Coordinator at Howard Center in Vermont—demonstrated exactly how this evidence-based approach works in practice.

The Stanley-Brown Safety Planning Intervention: From Research to Practice

The Safety Planning Intervention, developed by Gregory Brown and Barbara Stanley in 2005, began as a component of Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention. What started as part of a larger treatment protocol has evolved into a standalone intervention with remarkable versatility. Today, it’s successfully applied across diverse populations, from individual sessions to group interventions.

The strength of this approach lies in its evidence base. Three to four meta-analyses support the effectiveness of safety planning interventions, providing the “proven treatments that work” that both SAMHSA and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) emphasize during Suicide Prevention Month. This represents a practical tool with demonstrated results in reducing suicidal behaviors and increasing treatment engagement.

How Safety Planning Works: A Collaborative Process

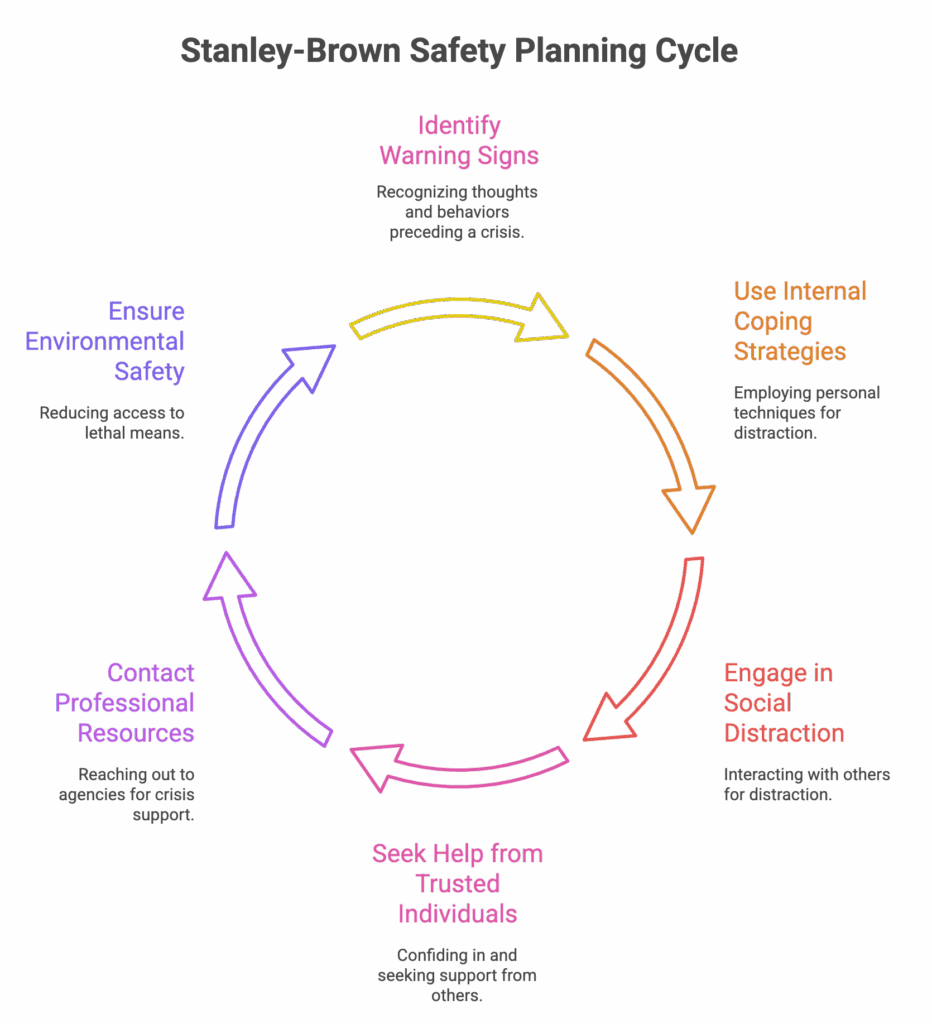

Margolis’s training included a powerful role-play demonstration with the fictional “Hal,” a 50-year-old construction worker experiencing suicidal thoughts. This demonstration revealed the intervention’s person-centered nature—an approach that aligns with Safer Society’s emphasis on collaborative treatment planning. Rather than imposing a generic template, the clinician sits beside the individual, working through six specific steps together:

- Warning signs: Recognizing the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that precede an acute suicidal crisis.

- Internal coping strategies: Identifying distraction techniques or strategies that a person can use on their own when they notice warning signs.

- People and social settings that can provide distraction: Engaging with others in social situations for distraction, without necessarily talking about the crisis.

- People to ask for help in a crisis: Identifying individuals whom the person can confide in and ask for support during a crisis.

- Professional agencies and organizations that can provide help in a crisis: Listing professional resources, with at least one needing to be available 24/7, such as the 988 National Crisis and Suicide Prevention Lifeline or a local crisis team.

- Making the environment safe: Developing a plan to reduce access to lethal means, including firearms and medications, by creating time and space between the person and the means.

Regarding these steps, Margolis reminds us:

“Suicidal crises are brief, and they don’t come out of nowhere. There are usually feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that lead up to the point of highest acuity. Safety plans aren’t forever; they’re meant to get people through suicidal crises that may arise in the near future, and the more personalized or individualized the safety plan is, the better the outcome.”

Integrating 988: A Resource for Crisis Support

It’s important to be aware of the value of the 988 call service. There’s an important distinction that many people aren’t aware of: 988 differs fundamentally from 911. While 911 might result in police response, 988 connects callers to trained crisis counselors who provide support without automatic emergency intervention.

Margolis described 988 as both a crisis line and a “warm line”—meaning individuals don’t need to be in acute crisis to call. They can reach out before reaching their most intense point of distress, making it a preventive resource as well as an emergency one. This 24/7 availability makes 988 an essential component of any safety plan’s professional support section.

Making It Work: Practical Implementation

Several practical insights emerged from the webinar:

- Safety plans must be accessible when needed—keeping copies at home, work, or photographed on phones

- Plans require regular review and revision as circumstances change

- Obtaining consent to involve support people strengthens the plan’s effectiveness

- Flexibility matters—if someone can’t identify internal coping strategies, move to social supports rather than forcing the issue

Moving Forward

The Stanley-Brown Safety Planning Intervention represents exactly what Suicide Prevention Month advocates for: evidence-based, person-centered approaches that provide hope and control during crisis. It transforms abstract awareness messages into concrete clinical practice, showing healthcare providers, counselors, and support workers exactly how to help someone develop a practical tool for surviving suicidal crises.

For those interested in learning more, resources include:

- The official Stanley-Brown Safety Planning Intervention website

- The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (call or text 988)

- Safer Society’s training on Safety Planning Intervention

As we observe Suicide Prevention Month, collaborative safety planning demonstrates that with the right support, evidence-based tools, and genuine human connection, people can find their way through a crisis to hope and healing.