Written by Robert J. McGrath, MA

Tragedies often trigger a range of responses, some beneficial and others not. In 2006, the sexual assault and murder of a teenager in Vermont shocked our small state. The governor quickly ordered probation, parole, and child protective services staff to review all cases involving individuals with past sexual offenses who were living with children and ensure the safety of those children.

In the wake of the Vermont tragedy, crisis interventions likely protected some children from sexual abuse. Yet, those interventions also likely resulted in unnecessary child separations from significant others, which may have caused children harm when a safety plan could have mitigated the risk. Balancing the risk of sexual abuse and the harm of child separation (see Figure 1) is extremely difficult, especially when a jurisdiction is operating in crisis mode.

At the time, I was the clinical director of Vermont’s programs for sexual offending. Alongside colleagues Georgia Cumming, the state’s probation and parole supervisor, and Heather Allin, a victim services specialist, we formed a team to assist front-line staff in conducting risk assessments and developing safety plans for the most challenging cases.

Two Key Issues

We felt the heavy responsibility of helping colleagues make high-stakes decisions and began reviewing the literature on conducting risk of sexual abuse assessments. Existing risk tools, such as Static-99R, focused on the likelihood that someone with a history of sexual offenses would sexually reoffend against an unspecified person. Our task, however, required more precision. We needed to assess an individual’s risk of sexually abusing a specific child, such as the risk posed by a woman’s live-in boyfriend with a previous sexual offense to abuse her child sexually.

The other critical issue was the potential harm of separating a child from those to whom they were positively attached to protect them from sexual abuse. We needed to assess the impact of such a separation, like removing an adult or a child from the home. Breaking strong, positive bonds between a child and significant others could cause the child serious emotional harm.

Assessing Risk and Protective Factors

Although we didn’t find a specific risk tool for child safety planning, we found substantial research on relevant risk and protective factors. These factors are categorized by the characteristics of (1) the person who has sexually abused, (2) the child at risk, and (3) the child’s primary caretaker.

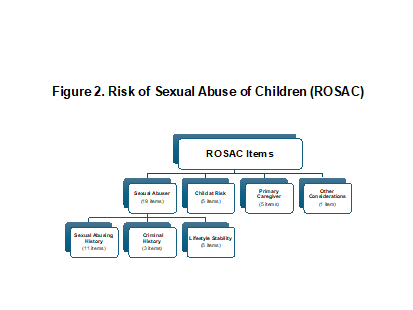

Initially, we used these risk and protective factors informally to determine risk. Over time, we developed a checklist to ensure all relevant factors were considered in each case. This eventually resulted in the creation of the Risk of Sexual Abuse of Children (ROSAC), a 30-item structured professional guide (see Figure 2).

Items are scored on a 3-point scale—present, partially present, or absent—but the ROSAC does not yield a total score. Instead, users apply their professional judgment to weigh and combine the risk and protective factors, resulting in three broad risk determinations: (1) no clear present risk, so no need for intervention; (2) some risk of sexual harm that may be managed with a safety plan, and (3) significant risk of sexual harm, warranting a prohibition of contact between the person who has abused and the child.

Limitations

Evaluating the ROSAC’s overall predictive validity presents an ethical challenge. Agencies usually restrict or ban contact between higher-risk individuals and children, making it difficult to determine whether higher-risk ROSAC cases indeed have a high rate of sexual reoffending. Ethically, we cannot allow high-risk individuals to be around children, like living in a home with a child, to test the tool’s accuracy. Nonetheless, although the effectiveness of the ROSAC as a whole has not been measured, each ROSAC item is empirically or clinically supported.

Conclusion

Professionals in mental health, corrections, and child protective services often need to assess the risk that a person who has sexually abused poses to a specific child and determine if, and under what conditions, the adult can safely have contact with the child. Without appropriate tools, professionals use their judgment to select and weigh different factors to make the best possible decisions. Our research indicates that we should focus on the characteristics of the person who has sexually abused, the child at risk, and the child’s primary caretaker. The ROSAC provides a structured method of incorporating a comprehensive list of evidence-based factors in these three domains to guide critical decisions.

Train with the Author

Robert J. McGrath, MA, offers extensive insights in his training with Safer Society, focusing on the evidence-based practices and risk assessment tools he has co-developed, such as the ROSAC and the Sex Offender Treatment Intervention and Progress Scale (SOTIPS). This training is designed for professionals in fields such as child protective services, mental health, corrections, and child advocacy who need to assess risks and develop intervention plans related to sexual abuse of children

Learn more about the on-demand training offerings below:

Intermediate Training:

Conducting Sexual Abuser Risk of Sexual Harm to Children Assessments Using the ROSAC

Length: 6 Hours

Cost of Training: $180.00

Credit: 6 CE Credit Hours

Purchase price includes access to training video and materials for 10 days.

Introductory/Intermediate Training:

How to Align Treatment Programs with Best Practices

Length: 6 Hours

Cost of Training: $180.00

Credit: 6 CE Credit Hours

Purchase price includes access to training video and materials for 10 days.